PARIS — Every place you’ve dreamt of offers unique disappointments. If you’re lucky, these drown in the rush of finally doing what you’ve wanted to do for so long you don’t remember not wanting it. Paris is of course one of these clichés, and its sirens are among the most seductive to have called out to me — which is to say I’ve been very lucky; my disappointments drowned in pleasure immediately. At 40, I’ve never been more grateful to be anywhere in my life.1

I haven’t written in a month because my husband and I decided to throw most of our old life in the trash and begin again. We’ve since sold nearly all of our furniture, put fifty-five boxes of books in storage, and sold our house. When we talked about this with acquaintances (friends know us better), they’d say, “You’re doing this because of Trump.” First, we don’t actually know what we’re doing — part of our jaunt is to figure out who we are, as people, after having gone through what we’ve gone through (more on that some other time). Second, while the current administration hasn’t exactly dissuaded us from making this decision, a President Harris, even if she desired it (she wouldn’t), would have been powerless to change this country’s narcissistic and vicious downward spiral. Genuinely, I don’t know where we’ll end up, or when, or how, but right now we owe ourselves a bit of wandering, and above all beauty — which a Midwestern city, I’m sorry to say, has starved us of more than any other aspect of life.

And the cliché, it turns out, is true: Paris is (probably) the most beautiful city in the world. It's a city of details — details which make it a city of the public. And it’s still very, very public. The civility with which one addresses and interacts with strangers is remarkable, especially since Americans are socialized to believe Parisians are rude.2 The metro runs every three minutes (the longest I had to wait was ten, after the fête on the 14th) and can take you anywhere in twenty or thirty. There’s a multitude of free public restrooms — since human beings tend to need to pee now and then, and don’t necessarily want to purchase anything just to do it. And the parks and squares are full of people actually enjoying the parks and squares, people reading and playing cards and talking to one another (and yes, gazing into their phones). I don’t want to over-romanticize one of the most romantic places on earth — I know about Paris’s problems, its prices, its housing, its militarized police, its constant flirtation with a rightward shift — but I did come here on a little vacation looking for something like society, and I’m grateful to have found more of it here than anywhere I’ve been in seven years.

Now, about those disappointments. Here’s the big one: A while ago, there was a news story about a man who’d been ticketed for having a speakerphone conversation on the metro. If you’ve read my essay on noise, you know this made the endorphins flow for me. It conjured a city where people were vicious to strangers about this kind of noise. But in reality, Paris is full of it — not on par with my own wild-west hometown, certainly, but definitely on par with New York or Los Angeles. Uncharacteristically — especially for a city on the forefront of taking noise pollution seriously — Parisians don’t seem to mind this version of it.

The next day, I bought an edition of Le Monde, in which Michel Guerrin had written a column about the transformation, over the years, of the annual Fête de la musique. What began in 1982 as a cultural indulgence to welcome summer — those who could sing or play an instrument were invited into the streets to share their talent, their voice — has become, he writes, just another excuse for people to have a rave in a town square, turning French cities into open-air trashcans.3 Conjuring Yves Michaud, Guerrin observes how, in the replacement of the performer with the spectator — the artist with the consumer — the festival has become another instance where “I feel” has replaced “I think.” What’s more, these events — pumping international music into public spaces — typically take place in the “grand centre et les quartiers touristiques” rather than marginal or unknown neighborhoods, by which Guerrin indicates neighborhoods where you’re likely to see your neighbors rather than adults who’ve come to treat your town as another disposable playground.

Admittedly, I read Guerrin’s article (it takes a lot of effort for me to read French) because I assumed it was a complaint about noise, and I’m a sucker for anyone pointing out the most omnipresent and masochistically tolerated pollution we all deal with on a day to day basis (pollution which does have adverse health effects, I never hesitate to point out — and which affects poor families far more severely than wealthy ones). But Guerrin’s article is really a complaint about values — and a public is predicated on values. For a French tradition, which celebrates French talent, to be replaced with a xeroxed spectacle full of international artists — many of whom perform in English, or simply perform in computer — is for an aspect of French culture to be occluded or erased by the banality of consumerism, which still rules its imperium from the United States, and specifically from California (the America of America, as Joan Didion called it). That people in one of the proudest cities in Europe watch thirty-second TV shows on their cellphones in the metro is another example of this same phenomenon — American ideals replacing the values of a society where the subway system is full of ads not for superhero movies or dating apps (there are some, I admit), but for museums, novels, and plays.4

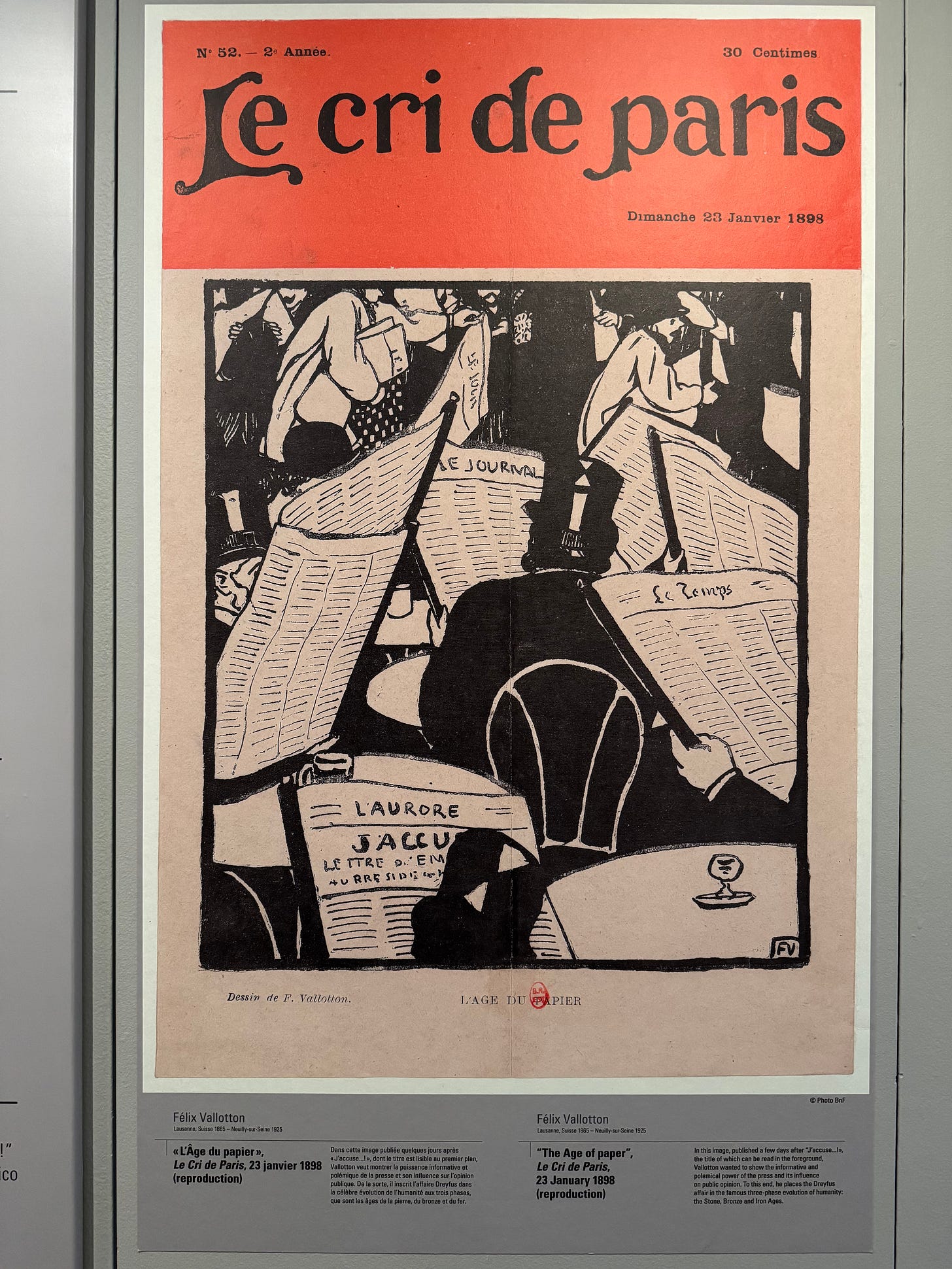

In January 1898, Le Cri de Paris — a Dreyfusard weekly — published a cover designed by Félix Vallotton. The Age of Paper depicts a café full of readers, each holding a different newspaper reporting on Zola’s J’Accuse. Vallotton’s design illustrates the power of the French press, whether conservative or liberal, royalist or socialist, antisemitic or pluralistic, to inform and influence a society.

This is, of course, my niche obsession — the way media can shape society, yes; but, in the case of smartphones as a specific form of media, the way corporations use technology to replace culture and community with a serializing consumerism.5 One of the more interesting contrarian responses I received to Image Control was someone asking me how social media is any different from television, if I’m so concerned by the effect that profiteering has on information and behavior — on social cohesion. And my answer is that, scale aside, it isn’t: Television, as it grew in influence and affluence in from the fifties to the oughts, was instrumental in taking America apart; and the more nakedly aligned with advertising, the more nefarious its effects. I don’t think it’s a big jump, either, from reality TV in the late nineties to the social media of the early oughts. The former brought viewers closer than ever to the fantasy that had always been there — What if I could be on television? — and social media is what gave us all the tools, however crude and rudimentary, to realize it. As far as any key differences are concerned with the rise of social media after seventy years of television, I don’t think you can underestimate scale and speed. TV simply has too many constraints (including legal ones) to be anywhere near as socially corrosive as a tweet — as the current president was happy to demonstrate during his previous term.

Right now, the United States is probably the ur-example of what happens to a country when you use technology, guided by neoliberal policy, to take society apart. It is also, from a corporate standpoint, an enormous success, and a model blueprint — to the point where Trump has threatened sanctions against countries which propose “discriminatory” measures against American tech companies by trying to regulate algorithmic learning models branded as “AI.” These models, of course, are the next exponential step in the corporate-driven individuation and isolation of human beings, an even more efficient and effective way to transform them from citizens to consumers. The EU, with its penchant for regulations and its 450 million people, is by far the largest obstacle to American tech companies (and American business generally). Therefore, the American right continues to use the language of rights, discrimination, abuse, and minority protections to clothe its predatory policies — which of course extend to turning European citizens, including Parisians, into mindless consumers of US-made content, or at least content linked to US-based advertisers. This kind of consumer-level tech is the avant-garde of imperialism in the twenty-first century, and almost all of its riches flow to American billionaires, who are more adept than ever at using the most powerful federal apparatus in the world the way gangsters use goons to muscle honest shopkeepers into extortion.

I doubt the French will see this; and it’s my hope that, in the next few months or years, there’s some movement or reaction against this kind of behavior in public — because if this is a public the French want to keep, the acceptable norms around smartphone behavior, and consumer technology in general, are a crucial boundary. I know this because I come from a city in which all norms and boundaries have been abandoned, where people bring speakers on public transit and leave scooters in front of accessible entrances, where the only place to find quiet is not a library (the place people go to watch YouTube, apparently) or a public park (too many aspirational and talentless DJs), but a private home — and only then, thanks to the un-mufflered and subwoofered cars racing around town, a luxury living space with soundproofed windows. The place I used to live in has no public left to speak of, and it feels less like a city, these days, than living in a hundred thousand different mediocre movies that everyone’s trying to star in but that nobody’s actually watching. I can confirm for you: this is not a spectacle anyone wants to witness, and, like so much else in American life, your tolerance for ignoring it only correlates with how much you’re willing to spend.

Thank you for reading, and thank you all for sticking with Entertainment, Weakly. I still haven’t turned paid subscriptions back on, as I don’t feel like I can be accountable to anything like a regular schedule as long as I decide to work on the road. Once I get settled I’ll give paid subscribers a heads-up. In the meantime, I am still working, and still available if you have any work you’d like to do together. Until then, <3

I suppose I knew it would feel this way. It’s probably why (one never knows why), in The Future Was Color, I gave Paris to George; I wanted to give it to myself.

I’m starting to wonder if the stereotypes about the French are taught to us to make us believe a more socialized, public approach to life — a life that’s nonetheless outrageously aesthetic and stylish — are simply propaganda to keep Americans complacent with their mediocrity. It’s similar, in fact, to how Midwesterners are raised to believe New Yorkers are mean. In both cities, you can find great kindness — as long as you don’t act like a horse’s ass.

This in addition to the kind of violence and “sexual aggression,” Guerrin writes, that one associates with a football match — reports of which were more numerous this June 21st than in years past.

For yet another example, look no further than the rentable scooters blocking sidewalks all over the world — a technology that masks itself as “for the people” when all it does is solicit childish behavior in adults, obstruct public walkways, and undermine actual public transit, all while funneling money to tech companies the way feudalists pay tribute to worthless lords.

A bizarre claim I see repeated again and again in cultural criticism (a.k.a. blogs) is the supposed absence of a monoculture, which usually means that not everyone sits down to watch Seinfeld or Friends like we did in the nineties. And while this is true, it’s hard to think of the overwhelmingly social media–inflected society of the United States as anything but a nihilistically consumerist monoculture.

Fwiw, I once interviewed a researcher who was studying the effects of neighbor noise and she was deeply distraught by how rarely anyone engaged with the topic. (Ultimately, my editor decided it was not science-y enough, proving her frustration 100% right.)

This is so inspiring.