Art on the Run

Clutching to the fugitive style in a technocratic world

Ms. O’Sullivan, the former Clarifai technologist, has joined a civil rights and privacy group called the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project. She is now part of a team of researchers building a tool that will let people check whether their image is part of the openly shared face databases. “You are part of what made the system what it is,” she said.

— the New York Times, July 14, 2019

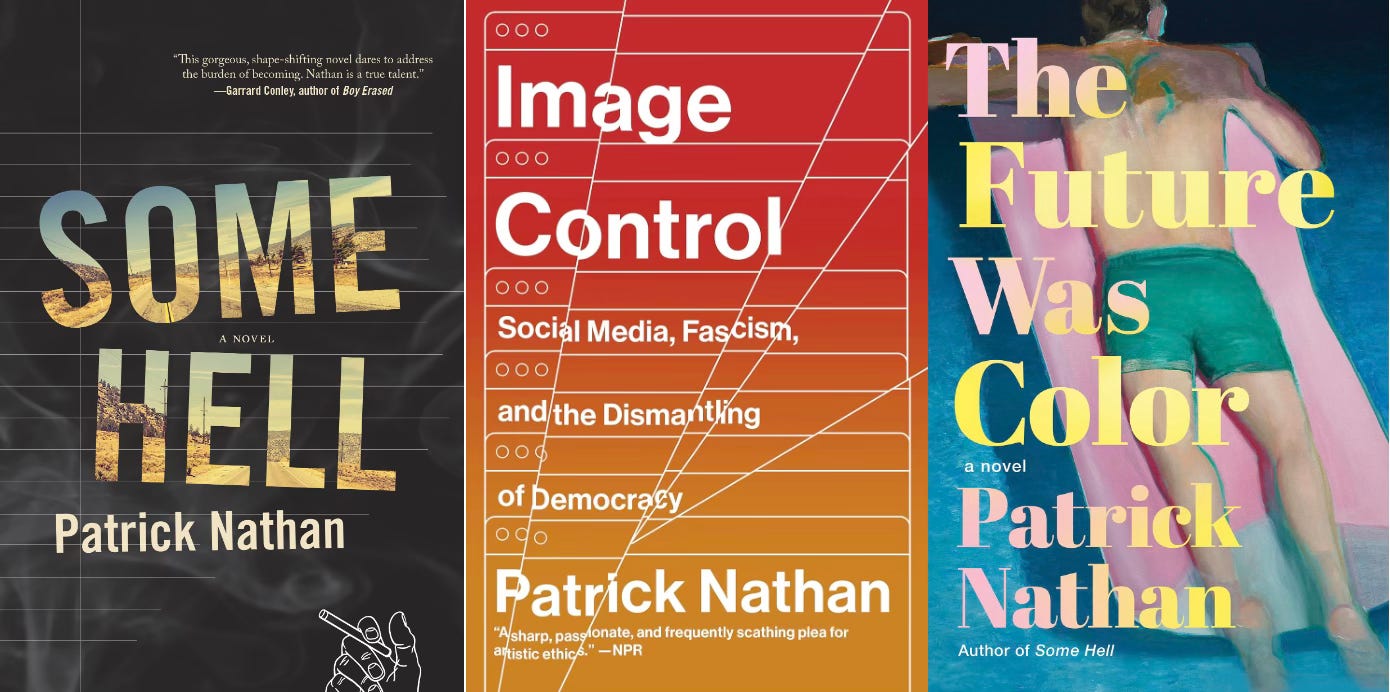

On Thursday, the Atlantic revealed to millions of writers that Meta Platforms, Inc., had pirated their books and used them to train its “artificial intelligence” model, Llama 3. Presumably, it’s these books — alongside thousands of films and trillions of photographs — that enable Instagram, for example, to spit out a mealy paragraph or repugnant image, should you ask it to do so. In fact, Instagram is constantly suggesting that you ask; whenever you type the word “imagine” anywhere on the platform, a pop up invites you to prompt “Meta AI” to generate more content.1 Since all three of my published books have been pirated by LibGen, the “library” Meta used to illegally obtain its “dataset,” this means that Instagram is constantly soliciting me to induce it to digitally vomit up slop formulated on years of my own hard work — not to mention millennia of cumulative hard work from other artists.

This information, as Alex Reisner reports, has only been made available because several high-profile writers are suing Meta for copyright infringement. While I’m not a lawyer, nothing could be clearer to me than Meta’s culpability2 in this particular case, and I hope these writers have the resources to avoid a precedent-evading settlement. As with previous lawsuits, the court records reveal that Meta has meticulously documented its own crimes.3 As Reisner writes, “Meta employees spoke with multiple companies about licensing books and research papers, but they weren’t thrilled with their options.” Acquiring rights, it turns out, was not only expensive and slow, but potentially damning: “A director of engineering noted another downside to this approach: ‘The problem is that people don’t realize that if we license one single book, we won’t be able to lean into fair use strategy,’ a reference to a possible legal defense for using copyrighted books to train AI.” Right now, that “fair use” defense is entirely speculative, and technically irrelevant in court: “Generative-AI companies say that their chatbots will themselves make scientific advancements, but those claims are purely hypothetical.” But it may not matter anyway, as Reisner points out:

Bulk downloading is often done with BitTorrent, the file-sharing protocol popular with pirates for its anonymity, and downloading with BitTorrent typically involves uploading to other users simultaneously. Internal communications show employees saying that Meta did indeed torrent LibGen, which means that Meta could have not only accessed pirated material but also distributed it to others — well established as illegal under copyright law, regardless of what the courts determine about the use of copyrighted material.

As we on the internet love to say, this kind of art theft is a “labor issue.” And it’s true: I’ve written three books and I deserve to be paid if people read them, profit from them, use them, quote from them, whatever. This labor issue is what the courts hope to resolve. What’s more, a company like Meta has demonstrated in court case after court case that it knows what it’s doing. Any judge worthy of the title can see that it’s time to obliterate and dissolve the company with insurmountable financial damages.

It’s a mistake, however, to think that intellectual property is the only victim of these enormous and pervasive “AI” models. Just because Meta is training its models illegally doesn’t mean that doing so legally would skirt around this more existential problem. Because I’ve already written at length about the ecocidal aspects of Silicon Valley content pollution, I want to focus here on the ramifications for art itself — on the social and individual activity of art, and how art made by human beings mediates our relationships with each other and with ourselves.

Art theft has a rich history, none more famous than its most heinous thieves — who also, as it turned out, kept meticulous records.

In June of 1939, 126 paintings and sculptures went up for auction at the Grand Hotel National in Lucerne, Switzerland. This is the set piece that opens Lynn Nicholas’s The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. These works, which included “Braque, van Gogh, Picasso, Klee, Matisse, Kokoschka, and thirty-one others,” as Nicholas writes, “came from Germany’s leading public museums.” All had been “banished from Germany as ‘degenerate art,’ but the Nazi authorities were well aware of their usefulness as a convenient means of raising urgently needed foreign currency for the Reich.” The atmosphere was bleak: “It was widely felt that the proceeds would be used to finance the Nazi party. The auctioneer had been so worried about this perception that he had sent letters to leading dealers assuring them that all profits would be used for German museums.” The proceeds, ultimately, “were converted to, of all things, pounds sterling, and deposited in German-controlled accounts in London” — still the banking capital of the world. “The museums,” Nicholas adds, “did not receive a penny.”

The Nazis went to enormous expense to fetishize art while denigrating artists, severing the art object — part of the culture or “the race” — from the intellectual and creative work that led to its existence. And in a Germany without artists, art must be stolen. This was one of Hitler’s many reasons for invading France. Art, for the Nazis, was a treasure or a status symbol; artists were liabilities — or simply Jews.

In Duty Free Art, Hito Steyerl writes acidly about the modern equivalent of this appropriation, particularly w/r/t the way pundits and politicians often suggest that artists are somehow “enemies of the people” in their “ivory towers,” unable to relate to the day-to-day activities of “normal” or average people: “The ‘anti-elitist’ discourse in culture is at present mainly deployed by conservative elites, who hope to deflect attention from their own economic privileges by relaunching stereotypes of ‘degenerate art.’”

The intent here, obviously, is to decouple the artist from the art, the labor from the product. The problem with these strategies, and what rich people — or the ruling class, or Hitler, or tech execs, or neo-Nazis like Elon Musk — never seem to see, is that art without an artist does not exist. This, in my view, is what the “labor issue” argument neglects. While I understand the instinct to cry foul when artists’ work is stolen to create slop intended to enrich a corporation, art is much more than labor — despite what a lot of artists themselves have proposed. Art has a signature that a manufactured item does not.

Writing of Duchamp, Harold Rosenberg recalled that “he had always been drawn to the notion of the artist as a craftsman — a term more venerable than ‘artist’… The modern artist fabricates not for individuals he knows but for an anonymous and ever-changing public.” In a later essay, on Dubuffet this time, Rosenberg reveals his personal scorn of this particular attitude:

As a champion of art by anybody, [Dubuffet] has directed his fire against art by somebody; that is to say, the figure of the artist… Dubuffet’s exaltation of ordinariness, and sub-ordinariness, fits him — as it does Warhol, who has also expressed the ideal of being like everybody else — into the pseudo-radical philosophies of anti-elitism which have been bringing art into accord with the aesthetics of big business and the mass media.

While Rosenberg sounds, here, like something of an aristocrat, he was a champion of workers’ rights. The problem is that he didn’t quite consider the artist to be a laborer in the same category as, say, an autoworker. Writing of the federal government’s enormous WPA Art Project, he recounts how, during the Depression, “‘income’ became translated into ‘job,’ and the artist was no longer a gentleman or bohemian pseudo-gentleman, but a socially employed expert.” With federal funds, the WPA commissioned approximately 10,000 artists, including Abstract Expressionist painters like De Kooning and Pollock, as well as socialist-realist muralists like Diego Rivera. When it ended, Rosenberg writes, it welcomed back to American consciousness “an essential dimension of art — I mean art as a vocation practiced for its own sake.” Losing the illusion of the artist as laborer, art “for the sake of the inner development of the artist came to the fore… Out of a job, American art forgot its mirage of a respectable social status and dedicated itself to greatness.”

“Greatness” is, admittedly, a lofty ideal — the kind of thing you scoff at when you have bills to pay or a day job keeping you away from your work. It’s the opposite of a rather pervasive contemporary sense of the artist — particularly the writer — in American life: the somehow psychologically well-adjusted fellow who pours himself a cup of coffee and puts his “butt in the chair” for a number of hours, then clocks out. This laboring writer, a kind of “craftsman,” is the expert that Richard Hofstadter foresaw in his 1964 book, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life: “Today knowledge and power are differentiated functions. When power resorts to knowledge, as it increasingly must, it looks not for intellect, considered as a freely speculative and critical function, but for expertise, for something that will serve its needs.” His professionalism, Hofstadter implies, is precisely what places the craftsman in service to power, or at least neutralizes his dissent: “The amenities and demands of academic life do not accord well with imaginative genius, and they make the truly creative temperament ill at ease… It is painful to imagine what our literature would be like if it were written by academic teachers of ‘creative writing’ courses, whose main experience was to have been themselves trained in such courses.”

While writing can be artisanal; and while there is an element of craftsmanship to assembling written works, literature is decidedly not a craft. Art always has a duality: a material object and something greater, something evasive. Pretending otherwise — simplifying the artist’s role to that of a laborer who puts in their hours and clocks out — reduces art to another manufactured product; and this transformation, which some might see as a justly Marxist analysis of the literary industry, functions quite differently and severely in the capitalist country we live in. If novels — even our most treasured works of national literature — are manufactured by laborers, they are fair game for the same revolutionary automations that have “disrupted” other industries over the last three hundred years.

Framing the theft of artistic intellectual property solely as a labor issue conforms to the capitalist’s logic — that labor can always be stolen or replaced. Workers may be able to seize the means of production, but not if the capitalist invents a means that no longer needs workers to produce. Alongside administrative assistants and factory workers, the writer as laborer becomes just another victim of “progress.”

There is a style of art ever on the run from technological advancement, which in the arts usually takes the form of reproduction and mass distribution. One (admittedly simplistic) way to read French Impressionism’s intensity of color is as a rebuttal against the dutiful realism of black-and-white photography’s “replacement” of portraiture. Once Kodachrome arrived in 1935, the heavy impasto of Abstract Expressionism and, still later, Fluxus, happenings, and conceptual art — all work of movement, evasion, dimension — asserted itself as the new unphotographable, the new unreproducible. Literary Modernism, in turn, went where cinema could not. Orchestral work tried atonality when radio and records gave way to pop. Call it — for its perpetual evasion, its refusal to submit to arrest — the fugitive style. In Benjamin’s terminology, it’s art that refuses to relinquish its aura, that resists or reacts against new “mode[s] of human sense perception” which are determined as much by “historical circumstances” as by nature. This is art that says, “I’m still here despite it all” and “Come find me if you can.” In soulless times, it clings to its soul.

This fugitive style of course has its corollary. While Duchamp articulated its philosophy (or, really, its indifference to having one), its most famous practitioner is Andy Warhol, the last celebrity Surrealist — not to mention the prophet of the surrealist consumer environment we now live in. A warholian surrealism of infinite copies, infinite blandness, and infinite cliché is the dominant style in every nation plugged into the neoliberal network, a network that categorically rejects friction of any kind. This is the style I’ve taken to calling bureaucratic. If bureaucracy, as Arendt put it, is “rule by Nobody,” a bureaucratic style is no one’s style. Rather than abrade or resist the connective apparatus of neoliberalism, works in the bureaucratic style embrace it: they are primed for immediate understanding and circulation. They aren’t works that have lost their souls, but works born soulless. Even as originals, they are copies.

Personally — and maybe arrogantly — I do not see myself in competition with Mark Zuckerberg’s computer. Despite stealing my work and turning it into data, there is nothing that man can do, not with all the servers in the world, to write on my level. That’s just a fact. Nor am I alone. In this sense, the tech industry is unable to replace or reinvent literature, nor the aspiration toward it. There will always be a fugitive style. But what these men can do is “disrupt” literature’s audience by strengthening the influence of the bureaucratic style, which makes it harder for fugitive works to exist. This bureaucratic function is what websites like Goodreads and Amazon and Instagram provide, a way to confuse the fugitive for the “problematic” or — that favorite of American anti-intellectuals — the “weird.” As Steyerl writes, this kind of “disruptive innovation” causes “social polarization through the decimation of jobs, mass surveillance, and algorithmic confusion.” An example she cites is the “noise” that digital slop or pollution can create: “If one wants not to take someone else seriously, or to limit their rights and status, one pretends that their speech is just noise.” Looking at Twitter in particular (Duty Free Art was published in 2017), Steyerl concludes that “Bot armies distort discussions on Twitter hashtags by spamming them with advertisements, tourist pictures, or whatever. They basically add noise… A bot army is a contemporary vox populi, the voice of the people according to social networks.” I would add that one doesn’t even need bots to create a “bot army,” just a sophisticated algorithm that slowly alters what users value and what concerns them. That most newspapers and cable news networks now report on Trump’s policies as though they’re the will of the people — the “vibes,” after all, have “shifted” — shows to what extent this kind of digital minority can bureaucratize the will of the people against the people. This register of subversion is at the heart of the bureaucratic style: Cynical and nihilistic by design, it disempowers those who’ve gone looking for meaning or authority in art by reinforcing the illusion that there is no agency, no resistance. You are invited to embrace your own subjugation and call this act of diminishment “relatable.”

The bureaucratic style — the self-nihilating oxymoron of “art by no one” — is precisely what the corporations training and pushing these generative algorithms hope to create. “AI” art is the digital reincarnation of the Nazi dream of art with no artists, of literature without writers. The danger here is not in its success, which is impossible, but in its sheer overwhelming and omnipresent volume — an incomprehensible content glut that introduces a new kind of perception or sensibility to human consciousness, and which further estranges art and literature from its potential audience. In thoughtlessly manufacturing so much noise, Mark Zuckerberg and his contemporaries will never harmonize that noise into music, but they will give real music, fugitive music, something to drown in.

What this means is that, if a friend tells you their partner has died, and you respond with the customary “I can’t even imagine how you must feel,” the platform cutely invites you to play with its algorithm.

“According to Zuckerberg,” Reisner writes, “the ‘Meta AI’ assistant has been used by hundreds of millions of people,” which is coterminous with hundreds of millions of people being exposed to hundreds of millions of ad impressions — Meta’s primary revenue stream — while using this generative algorithm. In other words, it’s obvious that Meta owes me and millions of other writers a lot of money.

In June of 2022, eight separate lawsuits claimed that Meta’s products had led to eating disorders, suicides, sleeplessness, and other serious psychological disorders among teenage girls. Records from these cases indicated that Meta was well aware of the psychological consequences of their products, yet pushed them anyway. This kind of internal proof of wrongdoing, by the way, is exactly what brought down the tobacco companies and changed the public perception of smoking — an almost unimaginable shift in the cultural consciousness that proves we can get rid of social media’s stranglehold on American life, if we want to.

Beautiful and right on! When are you going to publish a book of essays about all of this?

RIGHT ON: “Personally — and maybe arrogantly — I do not see myself in competition with Mark Zuckerberg’s computer. Despite stealing my work and turning it into data, there is nothing that man can do, not with all the servers in the world, to write on my level.”