Faithless Reading

Culture will never be data

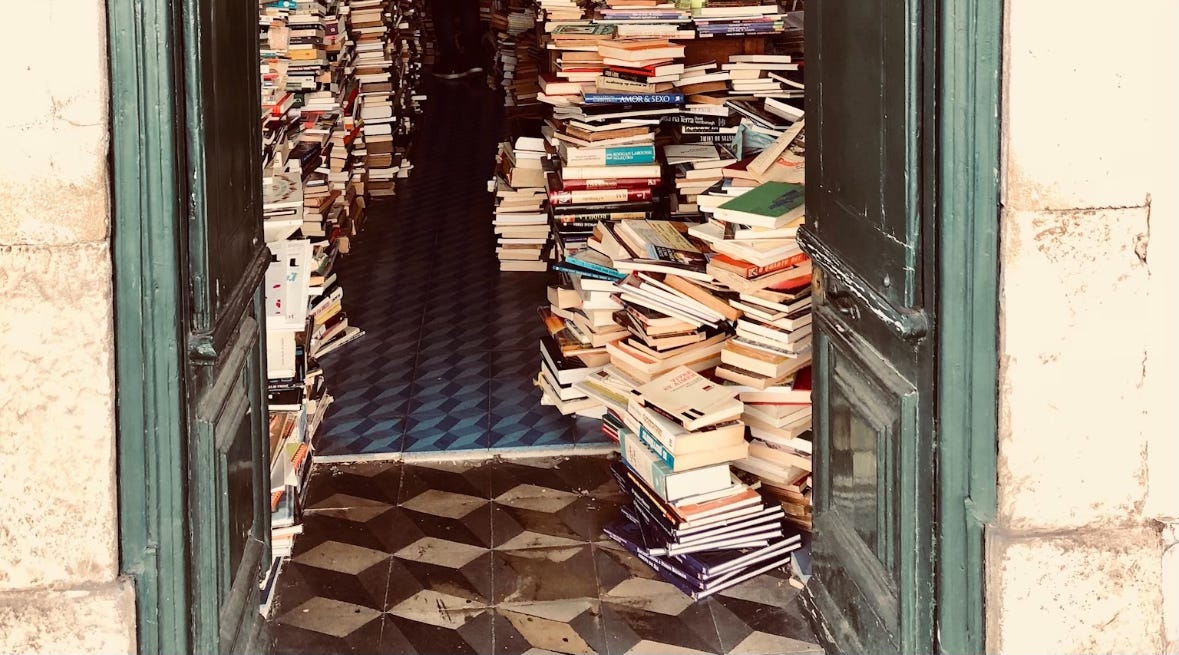

In this age of marvels, it’s easy to forget that a book is a manufactured product. Printed with soy– or petroleum-based inks and bound with polyvinyl acetate, these objects arrive in retail storefronts with flecks of dust or paper, nicked edges, and a damaged copy or two. A packing list instructs booksellers how to inventory them, as well as when to sell them; later, an invoice confirms the bookseller’s discount. These figures are set and negotiated, generally, by a robust sales force. Marketing teams determine how to “frame” the book, what stores or communities to sell it to, and ultimately its readership or intended consumer. All of this investment, labor, and manufacturing takes place after an author and editor have finalized the manuscript; after a copy editor and a proofreader have each taken their turn; and after a designer and a production team have formatted the words on the page, determined what fonts to license, how to break chapters or sections, and designed or commissioned a cover. Obviously, before any of this takes place, someone has to write the book and send it (or pitch it) to an agent. In the United States, this activity – warehousing, printing, logistics, sales, marketing, legal, editorial, representation, and so on – is a $25 billion industry.

This reminder, that publishing is manufacturing, is one of the tangential assertions of a recent essay by Yasmin Nair, published earlier this month in Current Affairs. “Writers are not creative geniuses spinning books out of thin air,” she writes, “but people who have to eat and find shelter while pursuing their work… We can (and should) also think about books and their markets as elements of a constructed reality.” This is one of her chief criticisms of the New York Times Book Review, whose “worst characteristics,” she says, “have seeped into that amorphous realm we might term ‘book culture’ – a world where unspoken traditions about how to read and whom to read and why have taken hold and authors are compelled to write in ways that conform to gendered and racialized expectations.” Part of this failure, she writes, is the way the Book Review emphasizes books from conglomerate publishers, which “perpetuates the material inequality so prevalent in the publishing world” and “replicate[s] its false and damaging hierarchies by only paying attention to stardom or the potential thereof.” In this kind of literary discourse, Nair says, authors – even nonwhite authors, who are “tokenized” in “essentialist ways, reducing them to mere standard-bearers of their perceived cultures” – are transformed into C-list celebrities, and books themselves fetishized as lifestyle commodities.

This celebrification of authors fits with the paper’s general ethos, as Nair points out:

The New York Times is not a paper of record as much as a guide to class assimilation and ascension: to read and absorb the Times is to learn (or so people hope) how to exist in a world that is in many ways brought into existence by the Times, one inhabited and controlled by the superrich.

A correction, Nair says, would be to return books to their industrial status – objects located “firmly inside the material world.” This applies to author advances, starting salaries, supply chains, benefits, and every other economic aspect of publishing. It’s a Marxist, I suppose, analysis of publishing: de-fetishizing the commodity and acknowledging the means that went into its production.

The problem, of course, is that books aren’t only industrial products intended for consumption by discrete demographics. Some of these manufactured objects are, simultaneously, works of art. This is the push, or reaction, in Christian Lorentzen’s essay “Literature Without Literature”: “Year after year our culture compels people to think of and understand themselves as consumers. This dreary view of life, which advertises itself as critical or at least conscious of commerce, capitalism, and complicity, quickly becomes another form of marketing, and when applied to our reading habits it amounts to a distracting narcissism, looking in the mirror when our eyes should be on the page.” To address the “categorical error,” as he calls it, of Dan Sinykin’s new book, Big Fiction (which argues that corporate forces have done more to shape literature than the writers themselves), Lorentzen clarifies exactly who is producing what: “Whereas creative-writing programs and the MFA system generally can reasonably be thought of as a site of literary production – places where novels are written and environments that in some ways shape the books written in their confines – the publishing industry is in fact the first stage of literary consumption.” By the time editors get their hands on a manuscript, the process is “more akin to tree trimming than tree planting,” and the author is indeed the producer of the works in question.

It’s the publishers who produce books, but the writers who produce literature – that ambiguous simultaneity where certain books are two things at once. This duality is the status, I think, of all things we tend to call art, and part of a critic’s job is to argue, in public, for or against this status with respect to specific objects (books, paintings, sculptures, films, albums) or events (plays, performances, dance). This has always been what’s wrong with calling an entire genre “literary fiction.” As a designation, it makes the critic’s use of the term – as Lorentzen uses it, for example, to distinguish literary consumption from other forms of reading – easy to misunderstand. This is why so many readers and writers from other genres tend to confuse the preference for literary fiction as elitism or snobbery, when in fact literary fiction is merely another genre with its own tropes and conventions, and those who seek it out do so because they’ve found a genre they reliably enjoy. Literary fiction is a marketing term for books that follow these conventions – that is, they are products aimed at a certain demographic, and nothing more. For literary fiction – or science fiction, or fantasy, or any other genre – to become literature, it needs that duality; it needs to be a marketable product and something else.

If Nair’s essay seeks to de-fetishize books as objects of discourse, Lorentzen’s seeks to re-mystify them as acts of literature. Neither of these arguments, I don’t think, is mistaken. Indeed, the books worth talking about are both de-fetishized objects and mystic wonders.

What books are not is lifestyle commodities. Unfortunately, most literary discourse has become fetishistic discourse, and most books are discussed in terms of how readers (buyers) relate to or identify with them. The marketing department at pretty much every publisher, no matter how small or independent, has learned to exploit this (sink or swim!), and the author’s identity or life experience – especially trauma, as Nair points out – is now the primary “sell” for what is fast becoming publishing’s real product: the authors themselves, whom publishers cast at social media users like handfuls of chickenfeed.

Contemporaneous with this shift from producing books to producing authors are the perennial justifications of reading as an activity. In the second decade of this century, for example, most literary magazines and book review sections published some version of the “empathy” article, citing various studies and quoting myriad scientists whose findings indicated that reading fiction was correlated with an increased capacity for empathy, which made it scientifically and socially useful to read novels – as if they were vitamins. This outside appeal is, in a sense, the fault Lorentzen finds in Sinykin’s project: “These warped views of literature reflect a shared tendency to explain art with minimal reference to the art itself… The dream is of literature that can be quantified rather than read.” Lorentzen also quotes serial data-monger Mark McGurl, whose self-described “method” involves “crudely convert[ing] historical materialism into a mode of aesthetic judgment, putting literary production in line with other human enterprises, such as technology and sports, where few would deny that systematic investments of capital over time have produced a continual elevation of performance.” If this were true, the enormous economic apparatus supporting the Iowa-to-Riverhead pipeline would be producing the greatest new novels published in America. And to be frank, it’s not.

Literary, as an adjective, implies a certain set of values. In my experience (author, editor, bookseller), most people who use that term don’t know what those values are – though not necessarily through any fault of their own. What’s happened to literature is a form of gentrification: local or endemic values have become confused, discarded, or even rejected in favor of outside values. This displacement of values is how books become data, lifestyle commodities, status symbols, or fetishized extensions of our consumer identities – and how authors, too, get sucked into this dehumanizing cynicism. Instead of working to transcend or expand genre, these marketing categories have come to turn authors themselves into genres – and readers along with them. It doesn’t take a great deal of imagination to see what political register human-being-as-genre falls into. And just as fascism has no faith in humanity, a critical discourse that grounds itself in neuroscience, data, and commodity fetishism has no faith in literature.

If books can be sociological, they are social – a demographic datapoint. They are also a “silent” and “solitary” activity, as Lorentzen says. But literature, in its very existence, proposes a public – those implied by discourse. These are the readers and writers who believe that books can transcend their ink, glue, and marketing copy. But to reject literary values in favor of marketing or pragmatic values (novels as vitamins, etc.) is to foreclose the existence of this public and cede agency to corporate influence. Instead of cultivating its own sensibility, a faithless readership becomes an exploitable resource. This is another aspect of the “constructed reality” Nair mentions. If audiences – conditioned to see critics as “elites” and informed opinions as attacks – can be trained, in this foreclosure of contestation, to reject literature (or cinema, in the case of Marvel fans), there’s no need for publishers to take risks on books that might also be works of art, and the audience for these products exists only as data to be mined and categorized. This is one constructed reality. If, on the other hand, a diverse and dispersed public proposes a loose, pluralistic set of literary values, and these values are continually contested, defended, attacked, and revised, agency is shifted back toward that public. It’s this public readership that constructs this other reality – a reality driven by its own endemic values, not warped and stupefied by the values of marketing or quarterly financial statements.

“Pleasure is why we read literature,” Lorentzen says, and pleasure, I’ve come to realize, is a strange aspect of being alive. Pleasure always seems to arrive as a simultaneity – as an and or even a despite. This movie is for idiots and it’s a lot of fun. That martini is magical despite what it does to your body. It’s risky to slip it in bare, yet – and so on. Pleasure, in its duality, is the art of living; and it’s in examining the qualities of that pleasure – where it comes from, how it acts upon us, what it does to us, how it leaves us – that one confers or denies upon the source of this pleasure the status of art.

This is, in a sense, the function of a critic – the one whose sensitivity to pleasure is, the story goes, more refined, more informed, and more articulable than the general readership, whose own sense of pleasure, in reading literature and criticism, is supposed to be heightened or expanded or instructed in some way. The artist makes an attempt, the critic evaluates it, the public agrees or doesn’t; and the artist and the critic and the public all leave this dialectic with a shift in their sensibility, which then informs future attempts and evaluations. Conversely, a discourse where books bolster a reader’s identity – or supplement their lifestyle, or improve their health and wellness, or substantiate some sociological claim – is a discourse that, in its appeal to non-literary values, denies a literary public. And with no public, there is no literature – only individuated consumer taste and the corporations happy to tell us what that taste is. Thankfully, more than a few great novels have told us where that path leads.

Good thoughts. Concerning critics, I find it easier to welcome their role when I think of them as "praegustator", as pretasters. Who have that heightened sensibility you speak of. And boy, it comes through training and attention. So one can see that a time and world that eschews training and attention —where all must be done fast to accrue advantage points— wouldn't welcome the slower, more rigorous and very attentive people. We have downplayed judgement and literature is where ethical and aesthetic judgement best happens. Obviously, we would like to encroach that realm with our cynicism as soon and as best as we can.

Once more, fine thoughts.

A particularly thoughtful essay, Patrick, thank you.