It’s four in the morning (the midst of October) and I’m writing you now — because I’ve just finished a novel, and can’t sleep. Sometimes it’s as simple as that, because I couldn’t sleep. So I got up and made coffee and I have no book to write.

Early this year, I received an invitation to a writing residency at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology. Two weeks in October to do absolutely anything I wanted, with no expectations — no talks, no classes, no lectures, no contributions. I didn’t even have to write, if I didn’t want to, as my generous host informed me. After a long summer in Europe, and approaching the end of my tourist visa with still no word on what to expect after that, I landed in the United States on the first, arrived here on the Oregon coast on the sixth, and immediately resumed work on a novel I’ve been carrying around with me for thirteen years. I finished it in eight days, sent it to my agent, and now arrive at an increasingly familiar feeling — that freedom is an abyss. I learned this after six weeks in France and another six in Portugal, where I was no one and every day could be any day. I don’t regret it, of course; sometimes you do want to glide through it, the abyss, and fathom just how deep it gets.

It’s not as if I’m one of those people who doesn’t know the next project. I have at least four lined up. And it’s not as if I don’t have other obligations (a deadline later today, in fact). But I do have terrible work habits. This novel is a testament to weeks and months and years of inactivity at a time, but always thinking about it, and then bursts like these of seven– and eight– and even ten–thousand-word days, getting up at five and writing all day long in nothing but sweats, eating peanut butter out of a jar.

Of course, the novel is a place to hide. Inexplicably, your goal is to take that hiding place away from yourself — to reveal yourself to the world all over again, once the work is done. For certain stretches of time, you go every day into this room you’ve built against the world. Its rules make sense to you, its sensuousness appeals to you, its characters even, in small, fragmentary ways, resemble you or parts of you. All of this is to say it’s a world that coheres, a world you can’t help but belong to. As I’ve written elsewhere, this is part of why I wrote The Future Was Color, an enormously sensual novel, during the pandemic.1 With this enormous and ambitious and draining project behind me, I now have nowhere to go — nowhere but the real world, the one that doesn’t cohere, the one I don’t feel like I belong to, that doesn’t look anything like me.

Somewhere in Canetti’s Book Against Death, he casts writing as a kind of chess game with the universe: “With every hour spent alone, with every sentence that you draft, you win back a piece of your life.” It’s an adversarial imagination of the writing process, not against anyone, per se, but against your silence or absence — against yourself. Elsewhere in the same book, he quips, “I have constructed a library that will last for a good three hundred years, all I need now are those years.” It’s a romantic notion, of course, since even Canetti knows that a good three hundred years would still involve around two-hundred-and-ninety of fucking around, and ten of work.

A few days ago, in an attempt to remember what I care about, I was listening to a conversation between Susan Sontag and Elizabeth Hardwick, generously archived by the 92nd Street Y. Trying to arrive at a distinction between the essay and the article, or the essay and an academic endeavor, Hardwick says, in her glorious drawl, “Everything you know, everything you are, goes into this writing — just as it is writing first of all — and all of your information is, I think, very important. Otherwise, it would be just a flat thing that no one would want to read.” It’s the authority, in other words, of a writer that gives the essay its strength, an authority earned, Hardwick adds, “by learning how to write.” Always this tautology — if you want to write “well-written work,” write well. Ah, of course — why didn’t I think of that?

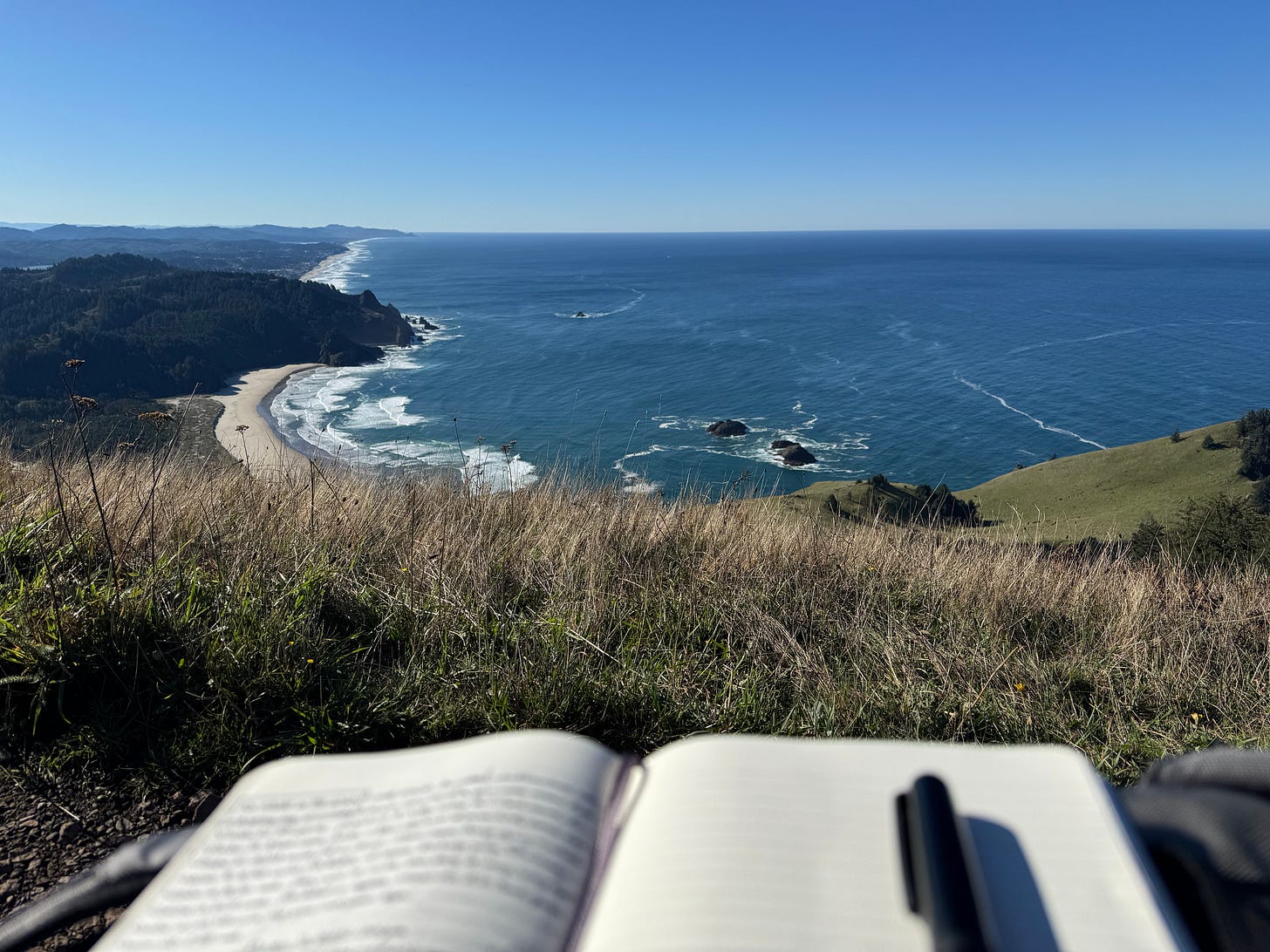

Here in the cool rainforest on the north bank of the Salmon River, I’m in a bit of shock. For months I felt shoulder to shoulder with strangers, most of whom I couldn’t understand, in cities with jackhammers and car horns and the braking of trains. Last night, I sat outside and listened to an owl for twenty or thirty minutes, an owl whose hoot was the hoot from movies and television, a real Hollywood hoot. On Monday, I left my cabin at nine in the morning, after working for several hours, and hiked out to Cascade Head. There was nobody around. I said nothing to anyone. For a while, I followed two small birds as they led me down a trail, and wondered if they knew something I didn’t; and then they flew away, afraid. I sat down and took out my notebook and wrote how everything had fallen apart, I didn’t know where I’d go once I returned to Minnesota, I knew nothing about the future, everything was uncertain. But no one knows anything about the future. You can make inductions based on patterns and information, but nothing’s ever certain. And anyway, I was looking at the ocean to my right and a river valley to my left, and I was here because someone had loved and admired my work — what was there to be so afraid of? Probably that love itself, I realize now, that admiration of something I’d already done; and now I was nearly done with the hardest thing I’ve ever tried to do, and afraid no one would love it, no would would understand it.

The strange thing is that I do know what Hardwick means — and what a lot of writers mean when they say “write well” or “learn how to write” (even though most evidently lack the authority). To want to write well: sometimes you can feel the need for it or urge toward it, like running your tongue along your teeth. It’s physical, maybe in the hand but not completely in the hand — a translation of the way a painter, I imagine, feels about the texture a brushstroke might create, with a certain viscosity of paint; or the way a pianist might crave the vibration of a certain chord, or a cellist the ring of a low note in her teeth.

This compulsion is strongest before the work is begun, and has always left me feeling like the first sentence, of an essay, should be its strongest, its most imperious. It made me realize that, despite the care and curiosity I’ve put into them, I haven’t really thought of these newsletters as essays, and that my recent lack of effort in shaping my ideas into essays, my avoidance of trying to place them with an ever diminishing handful of magazines, has left me feeling clumsy — physically clumsy. One thing Hardwick notices has vanished in her contemporary mediascape is the “familiar essay” of a certain quality: “When you think of Lamb, or even Montaigne, to some extent, that is now the sort of province of hacks, I would say, writing a little bit of advice or writing on marriage or in a rather shallow and quick journalistic way.” With their reliance upon the personal, upon the voice, upon the familiar — “Hey, it’s me” — maybe these newsletters have become the province of hacks, or at least of one hack.

This isn’t to say I don’t find them useful, these newsletters, or that I don’t enjoy writing them. Hack writing has a form to it, and like any form can take you places you don’t expect. A hack thing to do, for example, is open the dictionary when you get stuck, where you can learn that “hack” (c. 1700s to denote a drudge worker) derives from hackney, an ordinary, every-day horse for general service.2 To hack also used to mean to ride such a horse for pleasure or exercise. What fun, to open a document and type what’s on your mind at four in the morning (it’s now half past seven; I’m a slow writer), but it isn’t going to win us any races.

This is maybe what underlies my suspicion of writers with the access and the network and the influence who loudly leave their editorial support behind and venture into the familiar pastures of Substack, who replace their more rigorous work with missives like these. It’s not that you have to choose, one or the other, but — to continue in horse parlance — keeping your eye on the race is important. Otherwise you get clumsy and tired. You forget how to hold energy in your hand (or your voice, if you dictate), and you lose the craving to make that first mark — a mark that, categorically, is supposed to last. That’s the point of the brushstroke, after all, the point of the sustained chord, and the point, even, at the tip of the pen: to leave a real mark in the rainbow black of drying ink. I’ve missed the mark.

Thank you for reading, and thanks for sticking with me. Before I go, I want to share this incredible essay from Chris Campanioni, who wrote about The Future Was Color for the Brooklyn Rail:

One cannot behold a work of art without gazing upon the violence that may also be obscured by it. Perhaps this is also Nathan’s disquieting assessment, by linking an undercurrent of queer art in New York City with popcorn Hollywood production through the figure of George and his aspiration for cinema to reorganize the coordinates of the possible… Nathan’s novel shows us how, in George’s alternative vision for cinema and his promiscuous version of a heretofore hidden postwar culture, the “work” of art is to in fact destabilize the aesthetic regime that it depends upon for its very identity.

Finally, while I do plan to write more “real essays,” now that work on my novel is behind me, I’m not quitting Entertainment, Weakly: I still have letters on the way about the antifascist possibilities in UX design, unwanted revolutions, stolen homes, the histories of used books, camera rolls, criminalizing the public, and more. The letters are always free but please consider a paid subscription, if you can, as it helps me live my life.

Thanks again, and more soon <3

The other reason is that I was avoiding work on the big novel I just finished. I’d created a procrastination novel so I didn’t have to work on the more difficult novel.

“Hackney” itself is derived from Hackney, in Middlesex, where nags were raised on pastureland in the middle ages

Well done.