Pride and Paperbacks

and an excerpt from The Future Was Color

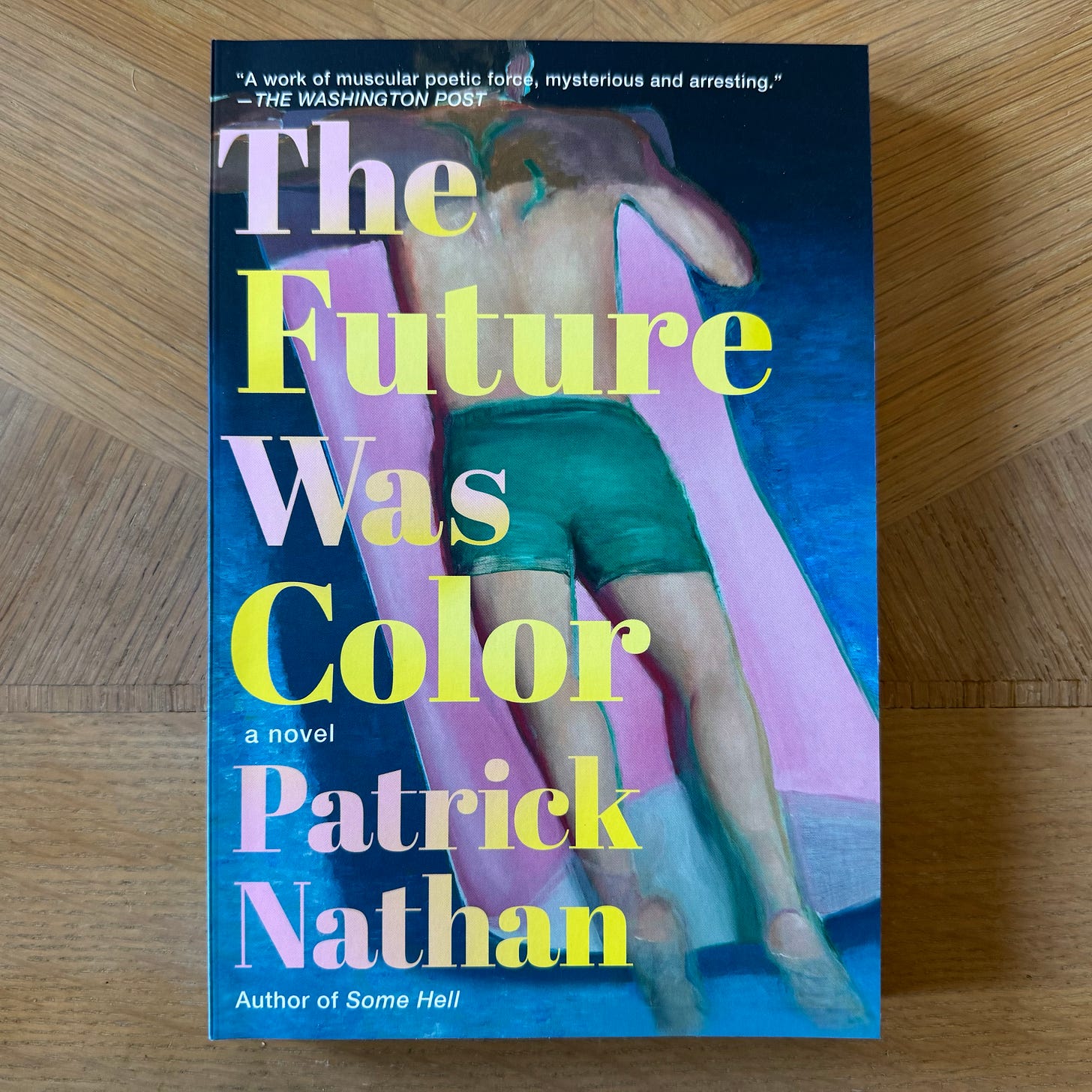

If you wait around long enough, the flags unfurl their colors, jeans molt into naked thighs, and every product, no matter how mundane, is somehow related to my marriage; and suddenly it’s lavender season all over again.1 It also means it’s been a year since The Future Was Color was published — which also means the novel and its “muscular poetic force” (WaPo) is now available in a gorgeous new paperback edition.

To celebrate, I thought I’d share an excerpt involving a bar, a drive-in screening of The Ten Commandments, and a little fellatio. At this part of the story, George (né György), a screenwriter and homosexual, is living with his friend Madeline at her beach house in Malibu. His colleague, Jack, has taken an active interest in his new social life, and invited him out for a drink — alone. Nobody knows who the narrator is.

If you haven’t yet read the novel, these paragraphs won’t spoil anything. If you enjoy them, please consider ordering a fresh paperback copy of the book from your local indie bookstore, or from the least problematic online retailer of your choice (Bookshop is always a great option). And of course, if you want a signed copy, feel free to order from SubText Books in St. Paul, and I’ll write whatever you want me to write on the title page.

At a piano bar on Sunset — the kind you sank down into like a dugout or foxhole — they drank bourbon and laughed at poor Madeline, poor Walt. What ridiculous lives they’d created for themselves, right George? Poor rich people, you had to pity them.

They shared the elbow of the bar and from there could see most of the long, narrow room — from its booths to its doorway, open to the street above. It wasn’t a walker’s city but there were, gliding across the golden lace of sunlight and junipers, a few passersby whose shoes and boots suggested, George thought, a realm that would never pay them any attention, no matter how loud or how talented the pianist. Down here the drinkers were mostly men; it wasn’t the kind of place anyone brought a wife or a date. George did not say this, but I’d like to make it clear that, in such environments, men like George feel fraudulent and anxious. They become imposters. It’s not simply a matter of belonging or not belonging but of confronting what is supposed to be “authenticity” with an even greater degree of artifice; where everyone else in the room — at last able to relax, to speak his mind — sets down his mask, ours is made heavier. To be alone with men is, for men like us, the call to give the performance of a lifetime. And we are called far too often, if you want my opinion.

But Jack, too, was an imposter here, and, while he couldn’t say it, George certainly knew it. Or he hoped it and called that knowledge. If one’s ears can’t help but hear, one’s eyes can’t help but say. It was them against everyone else, he imagined, and for the first time in a bar full of jazz and cigar smoke and the vilest jokes imaginable, George was relaxed; he could enjoy, he told me, his drink, his chat with an old and close friend.

So he drank perhaps more than he should’ve.

“She’ll never admit it,” he told Jack, “but Madeline was born without a personality. It’s tragic but she manages, she gets along, as you say.” He smiled at his own cleverness, pleased even before the analogy left his lips: “She resembles one of those birds who build everything out of refuse. A nest full of other people’s things, their stolen jewelry and discarded keepsakes.”

“But Georgie, she can’t help it. She just finds you so interesting.”

Georgie. So close he could almost hear his real name knocking around in Jack’s throat. He leaned into the drunkenness in his smile, which wasn’t as severe as he made it seem; he just wanted to be liked, to be enjoyed.

“Seems hard to believe all they do is drink and eat and go to parties,” Jack said. “Well, and act, I suppose. In fact Walt especially seems to do a lot of acting. I imagine he and that — that kid that was with us, what was his name?”

“Jack.”

“Hmmm?”

“No, his name is also Jack. We call him Jacques.”

“Cousteau.”

“Oui, comme ça.” George saw the vulnerability — where, after all, did Jacques come from? — and he lifted his glass to hold open the thought, the space, until he found something innocuous to fill it. “Madeline” — he forced a laugh — “she says this all the time, ‘I collect people.’ As if we are just things? Things, Jack.” His Madeline voice, a little higher and geographically ambiguous, as if he weren’t sure if he were making fun of an American or a Brit, made him blush. He’d never used it in front of another person.

Jack signaled the bartender. “What kind of people?”

“Oh,” George said. He was unprepared, grateful to earn a question from the one man whose questions were, right then, the most valuable in the world. The bourbon had coated his memories like spilled-on photographs and papers, and he thumbed frantically for something he could recognize, something not blurred into abstraction. “You know . . . collectible people, I suppose. Artists, actors and filmmakers, scientists, ex-convicts, émigrés, journalists, musicians, dancers, men who ride in boxcars . . . There’s a farmer, I believe. Once, a circus woman, I don’t remember her affliction.” The bartender filled their glasses another two fingers and Jack thanked him with a nod. George, with no lack of awkwardness, held his glass until Jack realized he wanted to clink them again in celebration. “Writers,” he added. Clink. A trembling sip.

“What kind of scientists?”

Had there really been a scientist? Had he said scientists? He supposed he must have, George told me. There are regions of the brain dark as forest gullies that send out warnings. He looked there. It took all his concentration and the look of it must have resembled pain. Jack touched his shoulder.

“It’s all right, George. I guess I’ve just been paranoid since I saw that car parked outside their beach house.” He reached over and moved George’s glass out of the way like a captured chess piece. There was a certainty in his hands; they never wondered where they did and didn’t belong, and George watched them with awe. “Maybe it’s time for a bite. Something to soak this up, hmm?”

As they gathered their coats and hats, Jack said, “It’s strange, about Ellman.” George must have looked confused, because Jack went on: “He disappeared the same time you did. I mean, you didn’t disappear. But he hasn’t been to work these last two days. Nobody knows where he is. Couldn’t get him on the phone, either. Not that anyone’ll miss him, but a man loves a good puzzle. Anyway, watch your step. Here we go.”

George remembered something Jack had said. “What car?” he asked as they arrived in the street. “Someone at the beach house?” But Jack didn’t hear.

Palms, billboards, stoplights. Everywhere losing that color like seaside rust as it flaked away into a deep, dark purple. They could’ve eaten anywhere, George told me — a restaurant, a diner, a burger stand, a Mexican food cart — he couldn’t remember. Nor did he remember the opening of the movie, only fading into it somewhere in the middle, Heston demanding the freedom of his people — the Jews, George thought as he watched this profoundly un-Jewish performance — but there was something even stranger. The film played on the windshield, and he wondered if there weren’t something else in that drink and that he was hallucinating it now, from memory, as Jack drove him home. But they weren’t moving.

He’d never, he explained to me, been to a drive-in movie, but he had heard about them. It was maybe the most American thing in America, that people drove out to these deserted stretches along highways and parked their cars and asked for snacks and craned their necks to watch a film they could see much better, and hear much better, from the comfort of a cinema. It felt like watching something happen here on earth through a telescope on another planet. Shadows swept back and forth across the bottom of the screen. In some cars, teenagers kissed furiously, their hands clasped on one another’s cheeks as if they didn’t know, or were too afraid, to let them travel elsewhere. Children ran up and down the gravelly walkways between the cars, screaming over the dialogue and the music that rattled the little speaker on Jack’s dashboard. When there was a gust of wind, the screen bowed as if it were breathing, and the film bulged with it — the actors shrinking or expanding, the sets distorted as if they were underwater. Cousteau, he remembered then, and turned to see Jacques — no, Jack — sitting there in the driver’s seat. He had one hand on a Coke that he held between his thighs, and the other, George only just noticed, resting along the top of the seat. If it were to fall forward, George realized, Jack would be embracing him. It was enough, with the liquor and the atmosphere and the incredible solitude — they were parked far, he noticed, from the other cars — for him to sweat, for his pulse to race.

“Hell of a thing, isn’t it, George? Supposedly the most expensive film ever made.”

And it was long. At two hours, there was an intermission; others left their cars to relieve themselves and seek out more beverages and snacks and stretch their legs. The less innocent stood and neatened their skirts and sweaters. Jack and George stayed put. It wasn’t until the film began to roll again that George noticed how hot the human body was, how it radiated heat. Ellman had disappeared. What did that mean — to “disappear” in a country like this one? The car grew warmer and warmer yet neither of them cracked a window. Jack shucked off his jacket and loosened his tie. George did the same. Jack unbuttoned the top buttons of his shirt. This George did not do. The windows had fogged — including the windshield, which blurred and softened the garish film. Did Edwards know? Is that why he’d called? At some point Jack had finished his Coke and set the bottle on the floor, his legs spread wide. His hand still rested in his lap and — just as he’d done at the office in what seemed a lifetime ago, another planet ago — began to run his thumb along a great, magnificent length that slept not so soundly in the shadow of his thigh. Had Ellman really left, that day, for a meeting? On-screen there were screams and there was music and there were great melodramatic speeches but George saw none of it. When a man is in heat, he told me, there is only one commandment. It never quite does us any good, but right then it seems our only salvation. Jack took it out and George moaned at the sight of it, and from there the rules were broken. It really was a hell of a thing, George told me. The film, of course — however it ended.

Thank you for reading! As I said last week, I’ve temporarily paused all paid subscriptions while I pack up my entire life and put it in storage for a few weeks. In the meantime, please consider ordering a copy of The Future Was Color; or, if you’re able, please spread the word that I’m looking for new clients — both for manuscript services and for copy work. Thank you for your patience. Entertainment, Weakly will be back soon with regularly scheduled essays and interviews.

This year, the jokes about rainbow capitalism are falling a little flat. After all, Pride merch grows ever closer to illegal in more states than not, banned as pushing an “inequitable” agenda that “disenfranchises” threatened heterosexual families. Even the cynical pretense of embrace is vanishing, and See you in hell you stupid fruit now seems more the mood of the first of June than of July.

Very happy to say I just ordered a copy from Subtext! Do I need two copies? Yes, yes I do. Congratulations on paperback day!