A Year in Reading

Highlights and lowlights of 2024

It was a good year to look at print. Words on a page gave me something to stand on this year, or maybe cling to like a floating door in the North Atlantic.

For someone who published a novel in 2024, I still managed to do a lot of reading (as opposed to vomiting, nail-biting, drinking, etc). As with most years, the majority of what I read were books I’d had on my shelf for years, books recommended in author interviews, books I decided to read for the second or fifth time. I started the year, in fact, with a re-read of Anna Karenina, which felt so much richer and deeper now than it did when I was twenty-four — who knew. Almost as though I was trying to claw my way back to something or some self, I re-read James Wright’s Selected Poems (for maybe the tenth time, I don’t know), Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, Carole Maso’s AVA, and Jean Rhys’ Good Morning, Midnight, all in a row. Later, I re-read The Sun Also Rises (still pretty good, it turns out), Bishop’s Geography III (again, for probably the tenth time), Louise Glück’s Averno (same), Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, Didion’s Play It As It Lays (her best book, unfortunately), Conrad’s Nostromo, and, of course, Salter’s Light Years (fifth or sixth time).

New to me, but a little less new to the world, were some wonderful surprises: Yiyun Li’s beautiful collection, Wednesday’s Child, Sigrid Nunez’s What Are You Going Through (maybe my favorite novel of hers, so far), Ruth Madievsky’s All-Night Pharmacy (a book I huffed like paint), Robert Boyers’ Maestros & Monsters (one of the best Sontag-adjacent books to come out in the last several years1), Elif Batuman’s The Idiot (one of the funniest novels of this very unfunny century), Alice Winn’s In Memoriam, Jonathan Crary’s Scorched Earth, Yanis Varoufakis’ Technofeudalism, Jeremy Cooper’s Ash Before Oak, Agustín Fernando Mallo’s The Things We’ve Seen, Zachary Carter’s biography of John Maynard Keynes, The Price of Peace, Dwight Garner’s delicious vacation of a book, The Upstairs Delicatessen, and Eileen Myles’ most recent collection, A Working Life. It’s exhilarating to think of all this talent in the world.

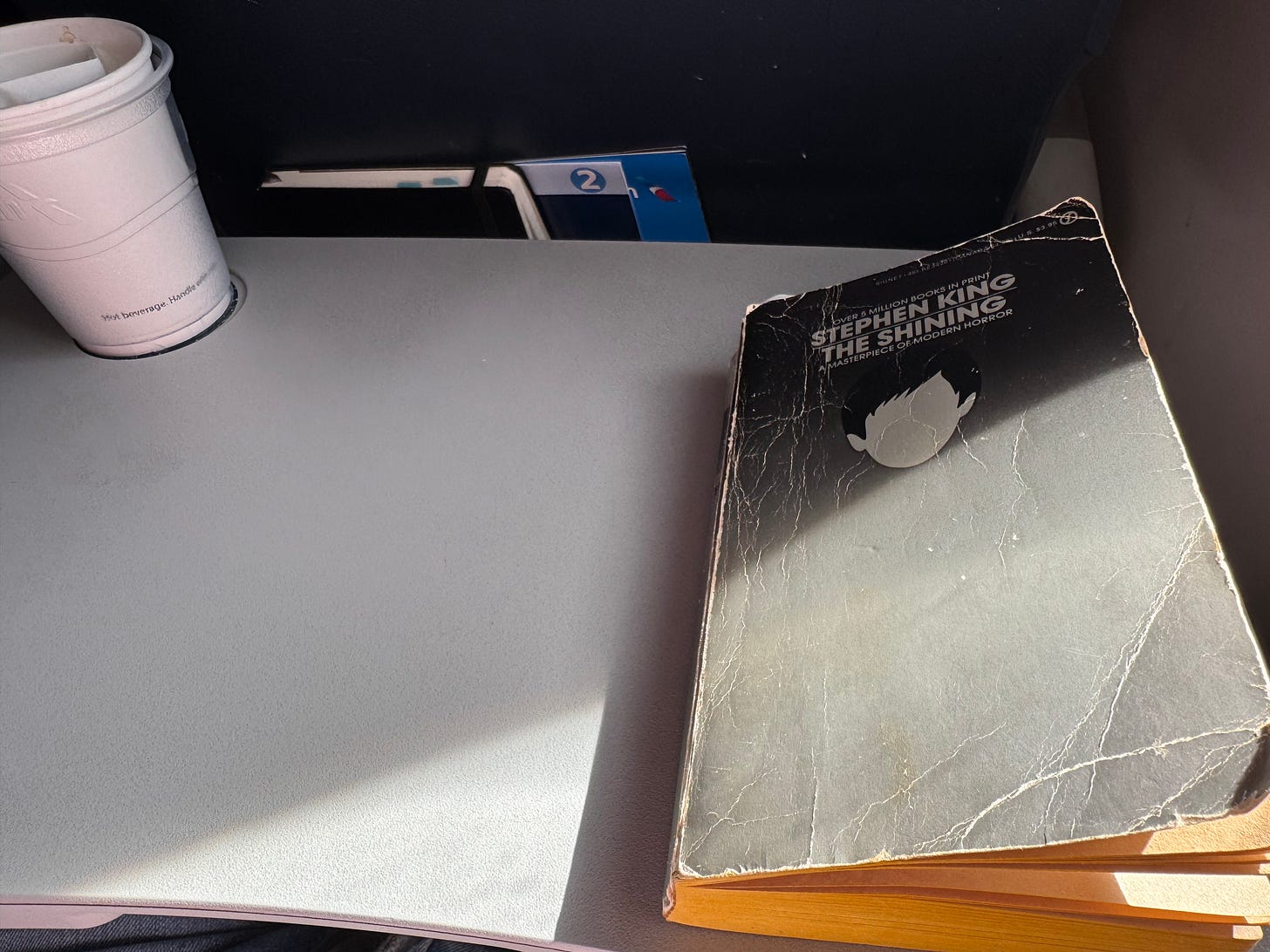

There were some older discoveries, too. I’m embarrassingly behind on DeLillo, but finally devoured Libra (after Mao II and Underworld last year). Lorrie Moore’s Anagrams is one of those unique books that’s hilarious — I actually laughed out loud every time I sat down to read it — until it’s suddenly, shockingly sad. Isaiah Berlin’s Four Essays on Liberty gave me a lot to chew on, especially in conjunction with Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism. I read Joseph Brodsky’s luscious essay about Venice, Watermark, while getting drunk at a Russian bistro in St. Paul, and Stephen King’s The Shining while folded up into an airplane. Somehow, I finally managed to read L’Étranger en français.

With discoveries there are also disappointments. Ariella Azoulay’s Civil Imagination felt too much like The Civil Contract of Photography to be of any significance. I read Ondaatje’s Divisadero and seemed to enjoy it, but couldn’t tell you a thing about it. The Name of the World is not the novel I expect from Denis Johnson, though I did like it well enough. While I was in New York, I stocked up on seemingly-out-of-print art criticism, including Harold Rosenberg’s Art on the Edge, which is certainly no Tradition of the New. Jessa Lingel’s Gentrification of the Internet offers a decent enough premise, but places too much faith, I think, in the overall idea of disembodying technology to be of much serious consideration. And like a lot of what gets called “autofiction” in American writing, reading Jenny Offill’s 2020 novel, Weather, in 2024 felt like scrolling tediously through old tweets with broken links.

How do 2024 books hold up to all this digging around in the past (and all these dead people)? Surprisingly well, it turns out.

All the World Beside, by Garrard Conley

One of my most anticipated reads of the year, Conley’s beautifully written novel centers on two men living in Puritan America, yet eschews a lot of the expected and anachronistic melodrama of the closet for a surprising, moving story about love and community.

Victim, by Andrew Boryga

The comic novel makes a comeback (again, very unfunny century we’re having) with this debut about a boy from the Bronx whose guidance counselor suggests that leveraging his “disadvantaged position” might earn sympathy from Ivy League admissions committees. The kind of satire that, by sparing no one, extends compassion to everyone.

In Tongues, by Thomas Grattan

In 2021, I had the pleasure of reviewing Grattan’s marvelous debut, The Recent East. In Tongues is even better — a story of gay ambition and entanglement set just far enough back in history (2000, sorry) that it feels like reading something lost. Swervy, sweaty, and fast-paced.

Love Novel, by Ivana Sajko

I touched on this (along with Heti’s Diaries) earlier this year, but Sajko’s novel about a destitute and miserable married couple living in post-communist Europe is a force.

Alphabetical Diaries, by Sheila Heti

More of an experiment than a narrative, Heti’s alphabetized journals read like a cross between a Markson novel and the babbling Cylon in her primordial ooze at the heart of every Basestar.

Hombrecito, by Santiago Jose Sanchez

Sanchez’s debut is beautiful written and dazzlingly structured, with just enough swerves to stay ahead of you. It’s a novel that, along with its protagonist, keeps reinventing itself as it goes.

Disordered Attention, by Claire Bishop

Maybe the most frustrating book I read this year, Disordered Attention — which analyzes the relationship museum– and theatergoers have with their phones and the ways that arts organizations should cater to this new form of “hybrid spectatorship” — totally neglects the role that tech companies play in this dynamic, ultimately capitulating to neoliberal values.

No Judgment, by Lauren Oyler

There is frustration, and then there is revulsion. At the very least, Oyler’s collection of essays — which she performs as a kind of literary stand-up for an audience that is obviously just Twitter — helped me formulate my thoughts on what I call the bureaucratic style. Oyler seems to have no will of her own in these essays, and tries to give that Twitter audience (which no longer existed by the book’s publication date) what she thinks they want.

Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, by Brad Gooch

This arrived right before a major Haring retrospective at the Walker in Minneapolis, so I read it as a kind of homework — which I enjoyed. Gooch really gets deep into Haring’s psyche and enriches one’s appreciation of his art, even if the material feels a bit thin for 400 pages.

Housemates, by Emma Copley Eisenberg

One of my favorite surprises of the year, Eisenberg’s debut novel is just a marvel. Ostensibly a road trip story about two queer housemates, this fluid novel never commits to a form or a subject, and instead dazzles you with new surprises in every chapter. Right in the opening pages, when the narrator decides — why not? — to walk right through a wall, I was hooked.

Lesser Ruins, by Mark Haber

I don’t know that anyone’s so masterfully channeled Bernhard’s bitter comedy the way Haber does in this remarkable, ambitious novel about art and obsession. Come for the narrator’s espresso machine incident, but stay for the terrifying, magnificent, and demonic Kleist.

When the Clock Broke, by John Ganz

I wrote about this one as well. Few books have so easily captured the far right’s talent for organizing and storytelling than Ganz’s book about the Republican Party’s transition toward finding “the enemy within” after the collapse of the USSR. Distressingly relevant.

Immediacy, by Anna Kornbluh

Speaking of the “bureaucratic style,” Kornbluh’s notion of immediacy almost gets at what I mean, but again doesn’t quite hit on the why or where. Still, it’s a wonderful read for those looking to understand what’s happened to form, in the arts — including fiction.

Villa E, by Jane Alison

In a novel almost as modernist as its subject, Alison re-imagines the relationship between Le Corbusier and the Irish architect and designer Eileen Gray, whose E-1027, in Southern France, drove the Swiss master mad with jealousy. Sparse, strange, and unique, at times it reads as though it, too, arrived in the 1920s.

Ripcord, by Nate Lippens

Easily one of the best novels I read this year. From its opening line — “Some people get the glory. Some people get the glory hole” — it deals one cutting paragraph after another, and never swerves from its vision. It actually reminded me of what Hanya Yanagihara said about David Wojnarowicz: “There is a distinction between cynicism and anger, because the work, while angry, is rarely bitter — bitterness is the absence of hope; anger is hope’s companion.”

Small Rain, by Garth Greenwell

As I wrote earlier this year: “I’m hardly the first to note how the roots of ‘author’ translate to ‘one who causes to grow.’ Greenwell’s skill in this novel is to show this expansion at work, the subterranean rivers of obsession that carve out our rock.” A beautiful, expansive, and surprising novel whose subject rises to meet Greenwell’s style.

Invisible Doctrine, by George Monbiot and Peter Hutchison

This short, fast-paced history of neoliberalism is indispensable for anyone looking to beef up their intel on the dominant (but constructed) ideology on the planet. Monbiot and Hutchison underscore the almost arbitrary nature of where we are, and how crucial it is that we change course.

The Picture Not Taken, by Benjamin Swett

Swett’s collection of essays — built largely out of his experience as a photographer — is roving, curious, but ultimately too thin. The first chapter is absolutely gorgeous, a narrative of a conversation held over dinner in a family home. But that style and intensity doesn’t last.

Entitlement, by Rumaan Alam

I read this one cover to cover in the bath. Alam’s sharp, biting novel about an ambitious young woman who imagines herself as a billionaire’s protégé builds to a shocking and uncomfortable climax.

Scaffolding, by Lauren Elkin

I’m surprised more people didn’t talk or write about this one, as it’s one of the best novels of the year. Elkin’s strange, hallucinatory glimpse into a woman’s tumultuous life as her building undergoes renovations, her husband moves to London, and her younger neighbor elbows her way into her life — and her bed — felt like a long, luxurious meal.

Creation Lake, by Rachel Kushner

My joke about this one is that it’s the Tár of 2024: It’s obviously great, but in its moral ambiguities invites most critics to contort themselves into often ridiculous, fatally online positions. Instead, try enjoying Creation Lake for what it is: a high velocity, high stakes meditation on the soul.

That’s it for this year, at least as of today. I’m at 89 books so far (and 300 pages from the end of Bleak House), but I’ll probably sneak in a few more before the year is out. If you have the time and the money, I do recommend buying whichever of these books sounds good to you, whenever and wherever you can — or getting them from the library. And if none of them sound like your thing, just buy mine and give it to a friend or donate it to a prison <3

And written by someone who is totally sane and gracious, as opposed to other biographers known to send unhinged and threatening emails.

I loved reading this!! and selfishly very happy that you opined on some books I’ve been meaning to read—Emma Copley Eisenberg’s Housemates (she’s so insightful in interviews), Anna Kornbluh’s Immediacy, Monbiot and Hutchinson’s Invisible Doctrine. Thank you for this post.

Also been very curious about Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding (though haven’t read it yet) and surprised there hasn’t been more discussion!

Honored to be in this company. Taking notes because a lot of these sound like books I need to read, too.