The Voice of Love

On Pablo Larraín's Maria

By adolescence, most of us have heard the story: that humankind created religion to explain an irrational world. It can take decades — if ever — to recognize what’s truer to experience: that instead we wanted to be dazzled by a rational one.

In a ghost story I never got around to writing, a diva feels her spirit called to this or that bedroom as one of her fans, always alone, plays an aria. Death is dark and roomless, the bottom of a black pool, and it’s her voice that illuminates a bed, a table, a desk, a sofa, a pile of records or CDs. Desperate to see, she always moves toward this light. The listener can’t notice her — they are simply alone, listening to music — but her presence in the room nonetheless disturbs them. They shiver when she’s close and wipe away unexplained tears. The light in the room grows brighter, grows farther; soon she can see out the windows, the streets where people are out living their lives. It felt, to me, like a good enough explanation of why music touches us so deeply, and I wanted to imagine how it must feel to be on the other side, to feel called.

To research this story, I ordered Cast a Diva from the library — Lindsy Spence’s “hidden life of Maria Callas.” I was looking for the clues or details that give fiction its texture, like the “tomato soup” the poorer New York artists in The Future Was Color make from ketchup packets and hot water at the Waldorf Cafeteria. But Spence’s book, aside from being badly written, falls into a common trap: everything that happens in young Callas’s life has its corresponding personality trait. (That new Mondrian biography is identically unreadable.) It’s the kind of writing that turns life into an equation or algorithm. I couldn’t finish it, and the story kept drifting around in various notebooks, never attempted. Like most stories.

Pablo Larraín’s Maria, which arrived in theaters last month, seems a parallel version of the story I imagined — which delighted me (now I don’t have to try!). In the last week of her life, a faded Maria Callas (Angelina Jolie) wanders the streets of Paris talking to a quaalude called Mandrax (Kodi Smit-McPhee) only she can see, whom she imagines as a documentary filmmaker interested in the details of her career. Unfortunately, even her imagination knows the media is misogynistic and scandal-obsessed. Though Mandrax initially asks about her work, he quickly shifts his focus and asks about her relationship with Aristotle Onassis; a miscarriage that the press called an abortion; and the way her mother treated her as a child. Meanwhile, Callas visits an empty theater for private vocal sessions with a conductor and devoted fan (Stephen Ashfield). These lessons are not in her head, and eventually attract a larger, unwanted, and ultimately cruel audience. She wants to sing again, without the obligation to perform. Her voice is frail and weak and her body is rapidly failing. “Your voice is in heaven,” a doctor tells her — right before she throws him out of her apartment.

“My mother made me sing. Onassis forbade me to sing.” Now she will sing, she tells Mandrax, for herself. Throughout the film, her attempts are met with pity. Even her housekeeper tells her, after an aria sung over an omelette, “It was magnificent, Madame” — in a way no one, not even Maria, can quite believe. Her butler, her doctor, and even her sister beg her to give up and enjoy what time she has left. Of course, this isn’t that kind of story. On her last morning, as her butler and housekeeper walk the dogs, Maria sings alone in her palatial apartment. Outside, all of Paris stops, and strangers stand frozen in place as they listen to Callas’s voice cascade from her open windows. Her doctor, of course, was right, and Maria dies singing, as befits someone whose entire life was opera.

Describing it this way, it seems so stupid and ridiculous. Watching it, I cried. But a lot of films can make you cry. Much more difficult to achieve: Maria made me believe in music.

Since the end of Modernism, most movements in the arts have been changes in the way art is discussed or marketed, not so much in the way it’s made. One consequence is that, in literary and artistic discourse (again, not in the works themselves), content has almost totally eclipsed form. A secondary consequence, which was inevitable given the first, is the demystification of the artist. The latter is perhaps the biggest, most concerning development in twenty-first century criticism.

First, the artist became a laborer — a sort of craftsperson whose long, difficult hours of work were to result in fair compensation, just like a coal miner or truck driver. This is an understandable reaction against the core demand of an internet-inflected media culture: that everything online should be free because it somehow isn’t real. Then, once the artist was a laborer — just a guy with a job like anyone else — their professionalism was now held to the same standards as other laborers, and any deviation in behavior meant getting “fired” by the strict boss of public opinion. Again, this is an understandable reaction against a culture that long excused artists, especially men, their abusive and antisocial behavior, as it was assumed to be the “price” that “we” all paid to have art in the world.

In reality, neither of these changes in the way people talk about or think about artists has altered the way genuine art gets made, nor the quality of that art. But it has, I think, affected the way the public — a.k.a. the people with the money to pay and support artists, or who at least seek out their work — thinks about and interacts with art. In fact, it doesn’t take much of a leap to conclude that evaluating works of art almost solely by their content — what they say or what they’re about — while simultaneously demystifying the work the artist performs — that a writer, for example, is just someone who puts their butt in a chair and goes to work every day — has brought us to our contemporary existential conundrum: that so little of this public recognizes what art is or how it works that they’re not only willing, but delighted, to ask computers to design works to their exact specifications.

Maria, thank god, is not a biopic. (I saw a headline that said something along the lines of “Fact Check: Here’s what Maria gets wrong about Maria Callas,” as if that were the point.) One of the many things that makes Maestro, for example, so awful is that it gives the “just a (horny) guy” treatment to Leonard Bernstein, unspooling his entire life as a simplistic pursuit of one baton or another. Yes, Maria touches on moments peppered throughout Callas’s life, at least as she remembers them, but it’s less a film about an artist’s life — or even about a real person — than it is about an artist’s love of her art, of the immense pleasure and pride it brings to her consciousness. Angelina Jolie’s Callas unquestionably adores music, and part of this adoration is wanting to contribute to music on her own terms. Yes, she is rude to others; yes, she is demanding and difficult; and yes, some of what she says and does would make headlines today as abusive and controlling behavior, but this doesn’t “humanize” her so much as re-mystify her, a welcome corrective of its own.

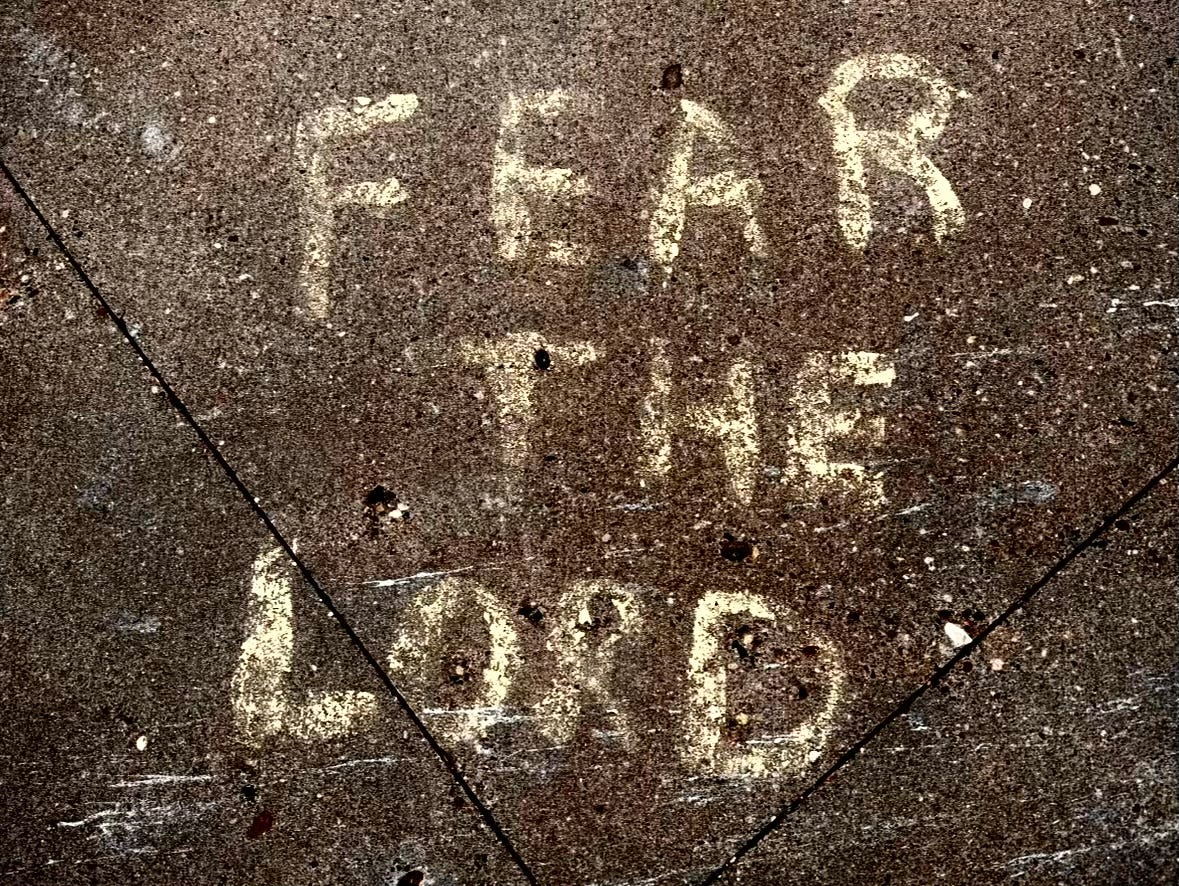

To put it simply, we didn’t evolve to be stupid. We belong to a curious, pattern-seeking, problem-solving species — a species that nonetheless goes to enormous lengths to obstruct its own understanding. To measure the quality of our intelligence against the extent of our works leads one to conclude that the human quest for meaning is better understood as a flight from it. To not know, to not see, to not understand: this, I think, is the genuine pursuit of spirituality, art, drugs, sex, and other total experiences. That other stuff — explaining fiction, say, as a “teacher” of empathy; praising music as paving our neuropathways — amounts to little more than the liquidation of the sacred into capital. The results of that, as we’ve seen, can be catastrophic. Part of what makes Maria work is that it occludes where music, where drive and talent, come from at all, and in doing so it returns immense pleasure to music itself. As I said before, it turns music into a matter of faith, and I left the theater lit with it. It made me remember not only what there is to love in music, but what there is to love in all the arts — a love that, like all love, doesn’t need to be justified, rationalized, quantified, or even qualified. But it does have to be maintained, which is what we’re looking for, whether we realize it or not, when we read or watch criticism of any kind.

Frankly, I need more maintenance in my life. I think we all do. Maybe that’s what 2025 is, for me, what it can be for you. Thanks for reading. Thanks for a great year. Thanks for everything.

A rare incisiveness, as always: "To measure the quality of our intelligence against the extent of our works leads one to conclude that the human quest for meaning is better understood as a flight from it. To not know, to not see, to not understand: this, I think, is the genuine pursuit of spirituality, art, drugs, sex, and other total experiences." Yes: a whole lot of human experience and striving can be understood a whole lot better if we see our own motivation as flight or evasion rather than seeking. Alas, I guess. But then again, how much great art would not even exist if we weren't so evasive of meaning and responsibility? Graham Greene's dictum that a writer finds his personal style when he confronts "the personally impossible" - the thing(s) he's personally unable to say or write directly - seems somehow relevant here too.

Some friends told me why I was wrong to love the movie. Thank you for helping me to understand new reasons why I loved it so. Beautiful piece!